|

Keys

to the Kingdom National Anthem The Office Touristic Sites |

Stretching east of Amman, the parched desert plain rolls on to Iraq and Saudi Arabia. This is a place where endless sand and barren basalt landscapes give proof to man’s ability to thrive under harsh conditions. The discovery of flint hand-axes in this desert indicates that Paleolithic settlers inhabited the region around half a million years ago. But the most remarkable remains of human habitation are the palaces built by the Damascus-based Umayyad caliphs during the early days of Islam (seventh-eighth centuries CE). During the height of the Umayyad dynasty, architecture flourished with the cultural exchange that accompanied growing trade routes. By 750 CE, when the Umayyad dynasty was overthrown by the Abbasids of Baghdad, a richly characteristic Muslim architecture was evolving, owing considerably to the cosmopolitan influence of builders and craftsmen drawn from Egypt, Mesopotamia and elsewhere throughout the region. Today it is possible to see many relics of the early and medieval Islamic periods in Jordan. Dotted throughout the steppe-like terrain of eastern Jordan and the central hills are numerous historic ruins, including castles, forts, towers, baths, caravan inns and fortified palaces. Known collectively as the desert castles or desert palaces, they were originally part of a chain stretching from north of Damascus down to Khirbet al-Mafjar, near Ariha (or Jericho). There are various theories about the purpose of the desert palaces, yet the lack of a defensive architectural design suggests that most were built as recreational retreats. The early Arab rulers' love of the desert led them to build or take over these castles, which appear to have been surrounded by artificial oases with fruit, vegetables and animals for hunting. Other theories suggest that they came to the desert to avoid epidemics which plagued the big cities, or to maintain links with their fellow Bedouin, the bedrock of their power. Most of the desert castles can be visited over the course of a day in a loop from Amman via Azraq. The following description details a road trip taking the northern route from Amman to Azraq and the southern highway on the return trip. |

|

|

|

Qasr al-Hallabat is located just off the main road about 30 kilometers east into the desert from Zarqa. It was originally a Roman fort built during the reign of Caracalla (198-217 CE) to defend against raiding desert tribes. There is evidence that, before Caracalla, Trajan had established a post there on the remains of a Nabatean settlement. During the seventh century CE, the site became a monastery, and the Umayyads then fortified it and decorated it with ornate frescoes and decorative carvings. Two kilometers past Qasr al-Hallabat, heading east, are ruins of the main bathing complex known as Hammam al-Sarah. The baths were once adorned with marble and lavish mosaics. Today, you can still see the channels that were used for hot water and steam. |

|

|

Azraq is located about 110 kilometers east of Amman at the junction of roads leading northeast into Iraq and southeast into Saudi Arabia. With 12 square kilometers of lush parklands, pools and gardens, Azraq has the only water in all of the eastern desert. The oasis is also home to a host of water buffalo and other wildlife. There are four main springs which supply Azraq with its water as well as its name, which in Arabic means "blue." Over the past 15 years or so, the water level in Azraq’s |

Azraq. © Zohrab |

| swamps

has fallen dramatically due to large-scale pumping to supply Amman and Irbid. This has

resulted in the destruction of a large part of the marshlands. While Azraq remains one of

the most important oases in the Middle East for birds migrating between Africa and Europe,

its declining water levels have led many species to bypass Azraq in favor of other stops.

The area was once home to numerous deer, bear, ibex, oryx, cheetah and gazelle, many of

which have been decimated in the last sixty years by overzealous hunters. Although the Iraqi border is far to the east, the town of Azraq has the feel of a border town, as there are no major settlements further east. There are a number of cafés and small hotels, along with a Government Rest House, in Azraq. |

|

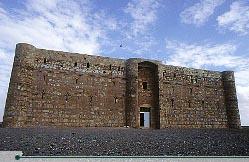

About 13 kilometers north of the Azraq Junction, on the highway to Iraq, you will find the large black fortress of Qasr al-Azraq. The present form of the castle dates back to the beginning of the 13th century CE. Crafted from local black basalt rocks, the castle exploited Azraq’s important strategic position and water sources. The first fortress here is thought to have been built by the Romans around 300 CE, during the reign of Diocletian. The structure was also used by the Byzantines and Umayyads. Qasr al-Azraq underwent its final major stage of building in 1237 CE, when the Mamluks redesigned and fortified it. In the 16th century the Ottoman Turks stationed a garrison there, and Lawrence of Arabia made the fortress his desert headquarters during the winter of 1917, during the Great Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire. The castle is almost square, with 80-meter long walls encircling a central courtyard. In the middle of the courtyard is a small mosque that may be from Umayyad times, along with the main well. At each corner of the outer wall, there is an oblong tower. The primary entrance is a single massive hinged slab of granite, which leads to a vestibule where one can see carved into the pavement the remains of a Roman board game. Above the entrance area is the chamber that was used by Lawrence during his stay in Qasr al-Azraq. The caretaker of the castle has a collection of photographs of Lawrence; in fact, his father was one of the Arab officers who served with the legendary Brit. |

|

|

Situated about 15 minutes south of Azraq, the Shomari Wildlife Reserve covers 22 square kilometers. The park is open daily from about 07:30 until around 16:00. It can be reached by following a desert road to the western side of the reserve, which is completely encircled by a fence. Numerous species of wildlife, including ostrich, gazelle, wild donkey, Arabian oryx and others inhabit Shomari. While the park has been able to protect these animals from being hunted, the lack of water in this area has caused these species’ habitat to shrink. Shomari’s great success story is Operation Oryx. This project has attracted worldwide recognition for its reintroduction into the wild of an almost extinct species, the Arabian oryx. With its two straight horns and black face markings, the white oryx once roamed the deserts of Arabia and the Fertile Crescent. Overhunting almost brought the species to extinction, but because of careful management Shomari now boasts around 200 Arabian oryx. The reserve has also fostered 14 ostriches from a single pair, and about 30 gazelles call Shomari home, as well. For more information about Shomari Wildlife Reserve, call the Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature (tel. 533-7932). |

|

|

Heading back towards Amman on Highway 40, Qusayr ‘Amra is about 28 kilometers from Azraq. This is the best preserved of the desert castles, and probably the most charming. It was built during the reign of the Caliph Walid I (705-715 CE) as a luxurious bath house. |

Interior of Qusayr Amra. © Michelle Woodward |

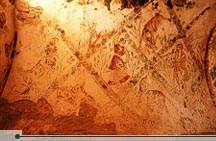

| The building may have been part of a larger complex that served to host traveling caravans, which was in existence before the Umayyads arrived on the scene. The building consists of three long halls with vaulted ceilings. Its plain exterior belies the beauty within, where the ceilings and walls are covered with colorful frescoes. Directly opposite the main doorway is a fresco of the caliph sitting on his throne. On the south wall other frescoes depict six other rulers of the day. Of these, four have been identified—Roderick the Visigoth, the Sassanian ruler Krisa, the Negus of Abyssinia, and the Byzantine emperor. The two others are thought to be the leaders of China and the Turks. These frescoes either imply that the present Umayyad caliph was their equal, or it could simply be a pictorial list of the enemies of Islam. Many other frescoes in the main audience chamber offer fantastic portrayals of humans and animals. This is interesting in itself because after the advent of Islam, any illustration of living beings was prohibited. |

Qusayr Amra. © Zohrab |

| The audience chamber, which was used for feasting, meetings and cultural events, leads through an antechamber into the baths. The caldarium, or steam room, is capped with a domed ceiling where a fresco lays out a map of the heavens, with the constellations of the northern hemisphere and the signs of the Zodiac. The two bathrooms have fine mosaic floors. |

|

Qasr al-Harraneh. © Michelle Woodward |

This well-preserved castle is located about 16 kilometers west of Qusayr ‘Amra and 55 kilometers east of Amman. The spot is marked by an assortment of tall radio pylons on the other side of the highway. |

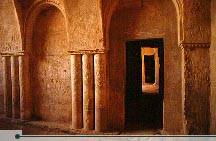

| Qasr al-Harraneh remains an enigma to archaeologists and historians. Some experts believe that it was a defensive fort, while others maintain it was a caravanserais for passing camel trains. Yet another theory is that it served as a retreat for Umayyad leaders to discuss affairs of state. With its high walls, arrow slits, four corner towers and square shape of a Roman fortress, Qasr al-Harraneh would appear to be a defensive castle. However, the towers are not large enough to have been an effective defense, and may have instead been built to buttress the walls. |

| The arrow slits are also cosmetic, being too narrow on the inside to allow archers sufficient visibility and too few in number for effective military usage. We do know that an inscription in a second-story room dates the construction of Qasr al-Harraneh to 711 CE. The presence of Greek inscriptions around the main entrance frame suggests that the castle was built on the site of a Roman or Byzantine building. |  Interior shot of Qasr al-Harraneh. © Michelle Woodward |

|

Just south of Amman, Qasr al-Mushatta offers an excellent example of characteristic Umayyad architecture. The castle is an incomplete square palace with elaborate decoration and vaulted ceilings. The immense brick walls of the complex stretch 144 meters in each direction, and at least 23 round towers were nestled along these walls. The palace mosque is sited in the traditional position, inside and to the right of the main entrance. Throughout, there is a powerful symmetry and axiality in the planning, with a tendency for compartmentalization, often into three sections. The vaulting systems are considered essentially Iraqi, but the stonemasonry and carved decoration is Hellenistic. Both influences are modified by their interaction, and this palace presents the most complete fusion of the two traditions in Umayyad architecture. Historians believe that Qasr al-Mushatta, the largest and most lavish of all the Umayyad castles, was begun by the Caliph Walid II—who was assassinated by forced laborers angry over the lack of water in the area. The palace was constructed between 743-744 CE, but was never fully completed. Qasr al-Mushatta is not on the Desert Castle Loop. To get there, take the Desert Highway south of Amman to Queen Alia International Airport. The castle is situated right at the end of the north runway. You must drive around the perimeter of the airport to get there. Turn right at the Alia Gateway Hotel as you approach the airport and the road will take you past two checkpoints and on to the castle. |

|

|

Qastal is one of the oldest of the Umayyad palaces, as well as one of the best preserved. The remains at Qastal include a wide variety of sites such as the central palace, baths, a reservoir, a mosque, small houses, a cemetery—the oldest Muslim graveyard in Jordan—and a dam. The central palace was decorated with stone carvings, and twelve semi-circular turrets buttressed and guarded the walls. The courtyard of the palace housed a central water tank. North of the central palace are the remains of the mosque. Interestingly, it is not oriented precisely eastwards facing Mecca. One kilometer east of the main complex are the remains of a stone dam, constructed to retain rainwater. Formed from the quarry which supplied stone for Qastal’s palace, the dam had a capacity of around two million cubic meters. Qastal was probably built in the early Islamic era by the Umayyad Caliph ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, who is known primarily for building the magnificent Dome of the Rock Mosque in Jerusalem. The palace of Qastal is very easy to find, 100 meters west of the Desert Highway near the town of Qastal, 25 kilometers south of Amman. |